- A gap between strategy and delivery – we know what we want to do, and we have the people and tools to do it, but we can’t seem to do it. We end up building something different to what we intended in the strategy. This may be a sign of weak strategy, or it may be a product ownership problem – translating business strategy into the products and services to be delivered.

- A gap between desire for pace of delivery and ability to deliver. We want to go at 100mph, but we can only go at 30mph. The pace of delivery may be constrained by capability, tooling, process, constraints, or simply capacity. It’s usually not actually a capacity problem, however. In technological domains, this is the realm of DevOps transformations and the practices that enable value to be delivered at high velocity whilst maintaining reliability and quality.

- A lack of organisational observability that results in poor understanding of value flows across the organisation, poor awareness of sociotechnical aspects of the system as a whole, resulting in problems that are known by teams taking leadership by surprise, if they ever become aware of them. A lack of systems thinking, combined with poor psychological safety across the organisation, results in executives only being told what they want to hear, or information becoming diluted as it flows “up”.

- Short termism – poor incentive structures (indeed, most incentives) or cultures mean that people are focused on immediate short term wins rather than long term value and outcomes. This is also manifested by an adherence to project methodologies where the delivery of value has a start and, specifically, an end date, instead of a long-lived product approach that provides people with greater ownership of outcomes, longer lived teams, lower technical and operational debt, and higher quality products and services.

- Quality issues. We can build the right things, but we can’t do it well. Conflicts of interest or capability issues mean that products and services are delivered, but they suffer from reliability, consistency or architectural problems. Technical and operational debt is high, and teams feel like they are always firefighting and dealing with unplanned work. An approach of late inspection rather than building quality in to the process is often part of the cause of this dysfunction.

- Poor organisational ability to learn. Systems, cultures and processes hinder people’s (and groups of people, such as teams or business units) ability to learn from failures and successes. The same mistakes are made repeatedly, and when successes do get made, the valuable learning from them is not institutionalised. Psychological safety, along with rituals such as retrospectives, may be lacking in this organisation.

- An excessive inward focus. Focussing too much on “what we do” rather than looking out at the world for challenges, opportunities, and a changing landscape means that opportunities are wasted and challenges can present existential threats to the organisation through a lack of capability to become aware of them, let alone adapt to them. A strong organisational cultural identity, whilst a powerful and valuable aspect of an organisation, can result in this dysfunction.

- An excessive outward focus. A focus only on the external means that market and environmental opportunities and threats are detected, but threats to performance or opportunities for improvement arising from inside the organisation are not detected, mitigated or exploited.

- A bimodal approach to value where the products and services delivered to customers far exceed the quality and features of those delivered to people within the organisation who are expected to use those services to do their job. We wouldn’t provide surgeons with blunt scalpels and expect a great result for the “customer”, but many organisations provide poor quality services and tools to employees whilst expecting high quality outcomes.

- A culture of fear over a culture of experimentation. An organisation that enforces behaviour or strives towards goals based on the consequences of failure or divergence from the norms, will move much slower and gradually grind to a halt. In these organisations, the safest thing to do is to comply with rules and take as few risks as possible, rather than suggest ideas, try (and risk failure), or admit mistakes.

The Accelerate State of DevOps Report 2021 – A Summary

The 2 state of DevOps reports each year aggregate the current state of technology organisations globally in respect to our collective transformation towards delivering value faster and more reliably. Or as Jonathan Smart puts it, “Sooner. Safer, Happier”.

The DevOps shift has been in progress for over a decade now, and whilst DevOps was always really about culture, the most recent reports are now emphasising the importance of culture, progressive leadership, inclusion, and diversity more than ever before.

Last year, in 2020, the core findings of the State of DevOps Report focussed on:

- The technology industry in general still had a long way to go and there remained significant areas for improvement across all sectors.

- Internal platforms and platform teams are a key enabler of performance, and more organisations were starting to adopt this approach.

- Adopting a long-term product approach over short-term project-oriented improves performance and facilitates improved adoption of DevOps cultures and practices.

- Lean, automated, and people-oriented change management processes improve velocity and performance over traditional gated approaches.

This year (2021), there are a number of key findings in the Accelerate State of DevOps Report, building on previous iterations:

- The “highest performers” continue to improve the velocity of delivery, through practices that enable teams to continually identify improvements to tooling, technology and process.

- Adoption of SRE practices improves wider organisational performance. Teams that prioritise both delivery and operational excellence report the highest organisational performance. Reliability is as important, if not more so, than short lead time for changes.

- Adoption of cloud technology accelerates software delivery and organisational performance, and enables the five capabilities of cloud native technology. Multi-cloud adoption is increasing, so that teams can utilise the strengths of each provider and improve resilience against risk of a single provider failure.

- Secure Software Supply Chains that integrate security practices into pipelines and processes enable teams to deliver secure software quickly, safely and reliably.

- Documentation is important. Teams that create and maintain high quality documentation are more able to implement technical practices, make changes, and recover from incidents.

- Inclusive and generative team cultures improve resilience and performance. Teams with psychologically safe and inclusive cultures suffered less from burnout during the Covid-19 pandemic.

View the entire 2021 Accelerate State of DevOps report here.

View the 2021 Puppet State of DevOps Report summary here.

And read here a summary of all the State of DevOps reports since 2013!

Health Promotion and HIV/AIDS pandemics the UK and South Africa

(Originally submitted as coursework towards my Masters in Global Public Health at the University of Manchester)

It is quite clear that the UK and South Africa are in very different situations with respect to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This is due in large part to behavioural changes in injecting drug users (IDUs) (Stimson, 1995) and adoption of safe sex practices including increased condom use amongst gay men, in the UK (Fitzpatrick et al, 2013).

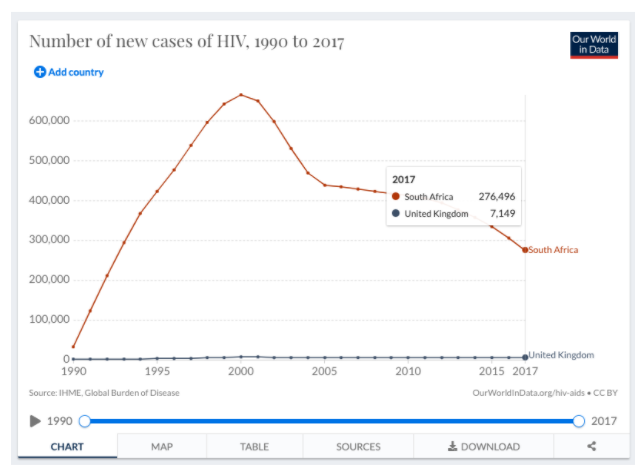

As this chart shows, the disparity between the two countries is huge. In 2017, there were 7,149 new cases of HIV in the UK, but 276,496 in South Africa.

Chart 1. New cases of HIV in the UK and South Africa, 1990 to 2017. Roser and Ritchie, 2019.

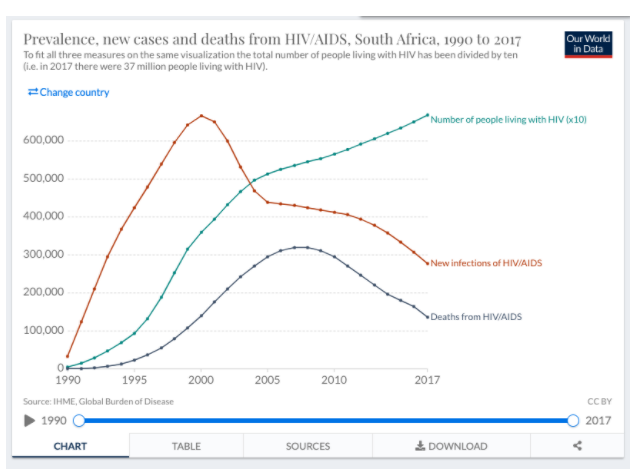

Whilst it is clear that new cases in South Africa are falling, prevalence of HIV/AIDS continues to increase as shown in chart 2:

Chart 2. Prevalence, new cases and deaths from HIV/AIDS in South Africa, 1990 to 2017. Roser and Ritchie, 2019.

The decreasing number of new infections in South Africa is due in large part to increased condom use and anti-retroviral treatment (ART) ((Vandormael et al, 2019), alongside higher engagement by women in the healthcare system – women who are more likely than men to request tests for HIV, request and access ART and therefore become non-infectious for HIV (Birdthistle et al, 2019).

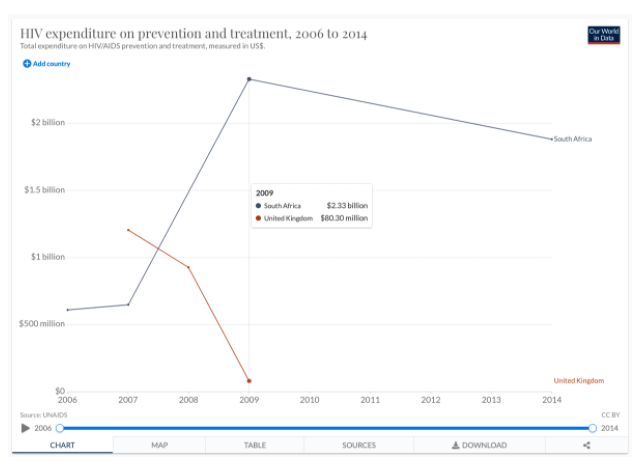

However, ART is expensive. Behaviour change is more difficult, but has a much greater ROI (Return On Investment). Due to the UK’s early approach of addressing behaviour change in high-risk groups, prevalence of HIV/AIDS has remained low, which, combined with increased safe sex and drug use practices, helps to keep incidence rates low (Stimson, 1995). Thus, the UK does not need to rely on large-scale ART interventions like South Africa, which is reflected in the costs each country must bear as shown in chart 3.

Chart 3. HIV expenditure on prevention and treatment, 2006 to 2014. Roser and Ritchie, 2019.

In 2009, South Africa spent $2.33billion on HIV prevention and treatment, whilst the UK spent $80.3million. It is unfortunately true that whilst prevalence is so high, ART is necessary to prevent significant increases in incidence rates, and increased cost-effectiveness may indeed be achieved by oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) – the provision of ART treatments to individuals in high-risk contexts (Alistar et al, 2014).

Whilst in South Africa, increased ART provision (and spending), including to those high-risk groups not (yet) infected with HIV, is necessary for the promotion of health, in the UK the story is somewhat different. The low prevalence of the disease means that safe sex practices – the continued emphasis on condom use – and expansion of access to HIV testing, alongside continuation of ART for people living with HIV/AIDS and the use of PrEP for those with an HIV-positive partner, could result in the near-elimination of HIV transmission (Brown et al, 2018).

Word Count: 461

References:

Alistar, S.S., Grant, P.M. and Bendavid, E., 2014. Comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in South Africa. BMC medicine, 12(1), pp.1-11.

Birdthistle, I., Tanton, C., Tomita, A., de Graaf, K., Schaffnit, S.B., Tanser, F. and Slaymaker, E., 2019. Recent levels and trends in HIV incidence rates among adolescent girls and young women in ten high-prevalence African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 7(11), pp.e1521-e1540.

Brown, A.E., Nash, S., Connor, N., Kirwan, P.D., Ogaz, D., Croxford, S., De Angelis, D. and Delpech, V.C., 2018. Towards elimination of HIV transmission, AIDS and HIV‐related deaths in the UK. HIV medicine, 19(8), pp.505-512.

Fitzpatrick, R., McLean, J., Boulton, M., Hart, G. and Dawson, J., 2013. Variation in sexual behaviour in gay men. In AIDS: individual, cultural and policy dimensions (pp. 129-140). Routledge.

Roser, M. and Ritchie, H., 2019. HIV/AIDS–Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids (Accessed: 15 June 2021).

Stimson, G.V., 1995. AIDS and injecting drug use in the United Kingdom, 1987–1993: the policy response and the prevention of the epidemic. Social science & medicine, 41(5), pp.699-716.

Vandormael, A., Akullian, A., Siedner, M., de Oliveira, T., Bärnighausen, T. and Tanser, F., 2019. Declines in HIV incidence among men and women in a South African population-based cohort. Nature communications, 10(1), pp.1-10.

Health System Service Delivery in Mexico and the Oportunidades programme

(Originally submitted as coursework towards my Masters in Global Public Health at the University of Manchester)

This discussion focuses on strengthening health system service delivery and accessibility in Mexico, via the “Oportunidades” programme. The Oportunidades programme is a useful one to explore, firstly because its horizontal approach “has led to increased health service utilization” (Blas et al p.155, 2011) and improved school attendance and nutrition of children across Mexico. Secondly, it has wider applications, as over 50 countries have since replicated the Oportunidades model (Lamanna, 2014).

Oportunidades has also been known as “Progresa” and “Prospera”, but for the purpose of this discussion, “Oportunidades” will be used throughout.

Context

Mexico is a Lower and Middle-Income Country (LAMIC) with high degrees of social inequality. It encapsulates many of the challenges experienced by countries of all income levels (Frenk, 2006). Poor children in Mexico are more exposed to health risks and hazards than their wealthier counterparts and have less resistance to disease due to undernutrition; reduced access to healthcare further compounds this inequity (Victora et al, 2003). A commitment to Universal Healthcare (UHC) is embedded within the constitution of Mexico, and was achieved in 2012 via a national health insurance programme called Seguro Popular (Knaul et al, 2012), alongside universal education, shelter and social security (Lárraga, 2016).

As such, Mexico is an excellent candidate for research into strengthening health systems, particularly through a Social Determinants of Health (SDH) lens. Under the direction of Julio Frenk, Health Minister 2000-2006, SDH and evidence-based approaches were used to develop policies which focused on equity and quality (Lancet, 2004).

The health system in Mexico is a hybrid model of publicly and privately financed and delivered healthcare and is segmented via three categories: salaried and retired citizens, self-employed or unemployed workers, and those with the ability to pay (Frenk and Gomez-Dantes, 2016).

Health System Service Delivery Improvement

Founded in 1997, Oportunidades is a conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme, funded through general taxation. Unlike vertical, selective interventions, Oportunidades takes a horizontal approach. This reflects the Alma-Ata statement that realising ‘Health For All’, “requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector” (WHO, 1978, I). It is intended to lift families out of cycles of poverty through combined healthcare, nutrition and education approaches, which aligns with the first five Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly, of No Poverty, Zero Hunger, Good Health and Well-being, Quality Education and Gender Equality.

The programme is centrally administered and initially covered 300,000 families across 12 states with a budget of 58.8 million USD (Levy, 2006). By 2006, the programme covered 5 million families across 32 states (Bautista Arredondo et al, 2008). The programme now covers over 6.4 million families, alongside training programmes to boost employment, and programmes to support the elderly (Sedesol, 2012).

Conditional payments are made directly from the government to the primary caregiver (usually the mother) of eligible children if they meet requirements, such as school attendance, registering with health clinics, accepting preventative healthcare, attending prenatal and postnatal clinics, and visiting nutrition clinics (Gertler, 2000). The money goes into beneficiaries’ banks accounts or onto prepaid debit cards and consists of contributions for nutrition, health and education, alongside food supplements. This incentivises the uptake of health system services while giving families autonomy over how they spend payments.

Crucially, education is integrated into Oportunidades – the strong universal correlation between education and health outcomes is well-established (Holmes and Zajacova, 2014). The programme further demonstrates its SDH credentials and alignment with the goal of Gender Equality, by providing larger incentives for girls to remain in school (Darney et al, 2014). Girls’ education is closely linked to health outcomes; women with higher levels of education have fewer children (Darney et al, 2014), experience fewer childbirth complications because they are more likely to seek medical assistance (Mainuddin et al, 2015), and have greater employment opportunities which help break the intergenerational cycle for families in poverty. Over medium and longer terms, this reduces the burden on health system service delivery.

Operational and strategic strengths

One of the programme’s strengths is that two of its key functions facilitate a robust evaluation and improvement feedback loop. Firstly, the well-defined target populations and sequential rollout aids in assessing effectiveness and provides researchers with a Randomised Control Trial (RCT) model (Ambroz and Shotland, 2013) which can compare treatment group families with control group families in locations not yet covered by Oportunidades. Secondly, information collected before payments begin is compared with later results, to establish longitudinal data about the intervention effectiveness (Skoufias, 2005). This has allowed service delivery improvements to be evidence-informed and targeted.

For example, continuous evaluation and improvement has enabled controlled scaling of the programme. Initially, only families that fell below an “extreme poverty” line in rural areas with schools and healthcare facilities within five kilometres were targeted (Ordóñez-Barba, 2019). Using evidence-based decisions, the criteria have since been revised to include urban families above the extreme poverty line (Lárraga, 2016).

Another strength is that the programme’s Operational Monitoring Model (MSO) combines national oversight with empowered, autonomous local delivery, which enables rapid response to feedback and systemic changes to service delivery. In 2010, mobile devices were introduced to carry out the ENCASEH (Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics of Households) eligibility survey. This increased the pace of eligibility interviews, and allowed staff to inform beneficiaries of their eligibility immediately. However, after staff reported negative reactions to delivering news of ineligibility, including having mobile devices destroyed or stolen and individuals refusing to let them leave, this was quickly changed to ensure that families were not informed until staff had left (Lárraga, 2016).

Through the MSO, an Operational Monitoring Report is produced every two months, and references 41 key performance indicators organised around themes of “i) enrollment of families; ii) continuity of beneficiaries in the roster; iii) education; iv) health; v) nutrition; vi) certification of co-responsibilities; and vii) payment of cash benefits” (Lárraga, 2016). The short reporting cycle with accurate indicators of performance has allowed for rapid evaluation of programme changes and early identification of issues or trends.

Although the programme strategy is defined nationally, it is coordinated through 32 state offices. Within each state, local organisations are coordinated within zones, and component “microzones” serve local families who are visited regularly by staff. This presence on the ground has facilitated communication with beneficiaries even in remote areas, aiding early problem detection and improving engagement (WHO, 2014).

By making direct payments to families, Oportunidades reduces the potential for corruption and improves financial efficiency. For every $100 allocated to the program, $8.20 is absorbed by administrative costs, compared with equivalent programs such as LICONSA and TORTIVALES where $40 and $14 are absorbed respectively (Coady, 2000). Building on that strength, payments are made to the mother “to guarantee that the spending of these resources would be directed toward buying food for the most vulnerable members” (Skoufias, 2005, p88), thus maximising the return on investment in service delivery.

Another strength of the programme, and one reason it has survived changes of government, is its transparency and lack of political alignment. In election years, there has been little or no mass enrollment, to avoid any suggestion that the incumbent government is “buying” votes of beneficiaries. In 2003, workshops and marketing campaigns adopted the slogan “In Oportunidades we all do our share”, to embed a sense of collective ownership and responsibility for the programme. There is therefore little political profit to be gained from a new government changing the scope of Oportunidades, or halting it altogether.

Success of UHC requires health-care service delivery to be managed efficiently (Sumriddetchkajorn et al, 2019). Financially, Oportunidades has proven to be efficient and stable at scale. Whilst the coverage and the budget of the programme has increased from 0.3million to 6.4million families from 1997 to 2017, the share of the federal expenditure never exceeded 2.3 percent (Ordóñez-Barba and Silva-Hernández, 2019).

Impact on service delivery and access

In respect to service delivery, the impact of Oportunidades is striking. Access to healthcare services has increased: more than 93 percent of beneficiaries in the programme have access to regular medical care, including preventative medicine and treatment (ASF, 2016, in Ordóñez-Barba & Silva-Hernández, 2019), compared to the average of 51.5% across the population (Gutiérrez et al, 2014).

Access to prenatal and postnatal healthcare increased by 12.2% over a ten-year period (Barber & Gertler, 2009). In the programme’s first year, healthcare clinic visit rates grew faster than in control areas, as did immunisation rates and prenatal and postnatal care. The increase in prenatal care also significantly reduced the number of first visits in the second and third trimesters of pregnant women (Gertler, 2000). Maternal and child mortality has improved significantly (Gertler, 2000) and the number of children suffering from malnutrition dropped from 25% to 8.2% between 2000 and 2015, “alongside a greater efficiency in relation to the cost of medical attention” (Ordóñez-Barba & Silva-Hernández, p.97, 2019). A 2004 study on Oportunidades’ impact on growth and anaemia in children, showed that haemoglobin levels were higher in children in treatment groups, and the programme was associated with better growth among the poorest and youngest infants (Rivera et al, 2004).

Participation in Oportunidades also correlates with increased diabetes mellitus detection and treatment (Behrman and Parker, 2011) through improved healthcare access.

Weaknesses in relation to health system service delivery

Oportunidades is not without weaknesses. Errors are prevalent in targeting, to the exclusion of eligible, and inclusion of ineligible, families (Ordóñez-Barba and Silva-Hernández, 2019). Some have critiqued the programme’s RCT methodology, suggesting that a quantitative approach that drives towards binary options of success or failure leaves little room for qualitative debate and nuance (Faulkner, 2014). Another criticism is that “contamination” of the treatment groups could occur through members of control groups immigrating to treatment group locations in an attempt to become eligible (Behrman & Todd, 1999).

The programme has been criticised for perpetuating “family-ism”, and the gender inequality inherent in assuming “the role of mothers in guaranteeing the effectiveness of public investments,” (Barba and Valencia, 2016, in Ordóñez-Barba and Silva-Hernández, 2019, p.86), though the same authors also recognise the programme’s commitment to addressing gender inequality through its potential to transform the traditional roles of women.

Some critics doubt how much impact CCT has on the trajectory of families in areas of low job availability. (Ordonez-Barba & Silva-Hernández, 2019) Likewise, it is of little use sending women to health clinics and children to school if the health clinics and schools are poor (Marmot, 2015; García-Guerra et al, 2019). To realise genuine improvements to health systems, the programme must be closely linked to economic strategy to ensure that it can improve “the productivity of families so that they are able to generate income through their own efforts and diminish their dependency on monetary transfers” (Presidencia de la República, 2014, para. 20).

Finally, some consider CCT programmes authoritarian. Whilst Oportunidades is intended to empower beneficiaries: “development can be seen as a process of expanding the freedoms that people enjoy” (Sen, 1985, p.3), imposing conditions upon payments can be seen as infringing on “freedom and dignity, creating disempowerment and power imbalances between programme providers and beneficiaries” (Scheel et al, 2020, p.718). Therefore, whilst Oportunidades aligns with the Alma Ata principles of “comprehensive healthcare for all” (WHO, 1978, VII, 6), it could be argued that its use of CCT conflicts with its spirit of self-determination.

Conclusions

Through their themes of “dignity, people, planet, partnership, justice, and prosperity for majority” the SDGs align with the WHO definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (Oleribe et al, 2015, Commentary). They therefore provide an appropriate ‘North Star’ for improving health system service delivery.

The Oportunidades programme supports the SDGs, particularly as they reflect the interrelationships and dependencies of escaping poverty through education, equality, economic development, partnerships and strong institutions (UN, 2015). Despite its critics, it has proven highly effective in strengthening health system service delivery and access, through its SDH approach.

Word count: 1999

References:

Ambroz, A and Shotland, M. (2013) Are RCTs (Randomised Controlled Trials) a new approach in evaluation? Better Evaluation. Available at: https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/evaluation_faq/rct_new (Accessed: 13 February 2021).

Barber, S. and Gertler, P. (2008) “Empowering women to obtain high quality care: evidence from an evaluation of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme”, Health Policy and Planning, 24(1), pp. 18-25. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn039.

Bautista Arredondo, S, et al. (2009) External Evaluation of Oportunidades 2008, 1997–2007: Ten Years of Intervention in Rural Areas (1997–2007), Vol. II. Mexico City: SEDESOL; 2009. Ten years of Oportunidades in rural areas: Effects on health services utilization and health status. Available at: http://www.oportunidades.gob.mx/EVALUACION/es/wersd53465sdg1/docs/2008/2008_volume_ii.pdf

Behrman, J. R., & Todd, P. E. (1999). Randomness in the Experimental Samples of PROGRESA (Education, Health and Nutrition Program); IFPRI Discussion Paper.

Behrman, J. and Parker, S. (2011) “The Impact of the Progresa/Oportunidades Conditional Cash Transfer Program on Health and Related Outcomes for the Aging in Mexico”, SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1941850.

Berwick D. (2004) Lessons from developing nations on improving health care British Medical

Journal 328 (11): 24-9

Blas, E., Sommerfeld, J., Sivasankara Kurup, A., & World Health Organization. (2011). Social determinants approaches to public health: from concept to practice. World Health Organization.

Buffardi, A. L. (2018). Sector-wide or disease-specific? Implications of trends in development assistance for health for the SDG era. Health Policy and Planning, 33(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx181

Coady, D.P., (2000) THE APPLICATION OF SOCIAL COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS TO THE EVALUATION OF PROGRESA; FINAL REPORT. International Food Policy Research Institute (No. 600-2016-40137).

Faulkner WN. (2014) A critical analysis of a randomized controlled trial evaluation in Mexico: Norm, mistake or exemplar? Evaluation. 20(2):230-243. doi:10.1177/1356389014528602

Fehling, M., Nelson, B. D., & Venkatapuram, S. (2013). Limitations of the Millennium Development Goals: a literature review. Global public health, 8(10), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2013.845676

Frenk J. (2006) Bridging the divide: Global lessons from evidence-based health policy in Mexico Lancet (368): 954–961

Frenk, Julio & Gomez-Dantes, Octavio. (2016). Health System in Mexico. Health Care Systems and Policies https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6419-8 Springer, New York, NY

García-Guerra, A., Neufeld, L. M., Bonvecchio Arenas, A., Fernández-Gaxiola, A. C., Mejía-Rodríguez, F., García-Feregrino, R., & Rivera-Dommarco, J. A. (2019). Closing the nutrition impact gap using program impact pathway analyses to inform the need for program modifications in Mexico’s conditional cash transfer program. The Journal of nutrition, 149(Supplement_1), 2281S-2289S.

GAVI CSO Factsheet 5 – gavi-cso.org (2013). Available at: https://sites.google.com/a/gavi-cso.org/gavi-cso-org/gavi-cso-hss-platforms/factsheets (Accessed: 31 January 2021).

Gertler, P., (2000). Final report: The impact of PROGRESA on health. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, 35.

Gutiérrez, J. P., Garcia-Saiso, S., Dolci, G. F., & Ávila, M. H. (2014). Effective access to health care in Mexico. BMC health services research, 14(1), 1-9.

Haux, R., 2006. Health information systems–past, present, future. International journal of medical informatics, 75(3-4), pp.268-281.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1386505605001590

Holmes, C. and Zajacova, A. (2014) “Education as “the Great Equalizer”: Health Benefits for Black and White Adults”, Social Science Quarterly, p. n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12092.

IFPRI (2002). PROGRESA: breaking the cycle of poverty. Washington, D.C., International Food Policy Research Institute.

Knaul, F. et al. (2012) “The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico”, The Lancet, 380(9849), pp. 1259-1279. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61068-x.

Lancet. (2004) The Mexico statement: strengthening health systems. 364: 1911-1912

Lárraga, L. G. D. (2016). How does Prospera work?: Best practices in the implementation of conditional cash transfer programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inter-American Development Bank.

Levy, S. (2006): Progress Against Poverty: Sustaining Mexico’s Progresa-Oportunidades Program, Washington, D.C., Brookings Institution Press.

Luccisano, L. (2006). The Mexican Oportunidades Program: Questioning the linking of security to conditional social investments for mothers and children. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 31(62), 53-85.

Marmot, M. (2015). The health gap: the challenge of an unequal world. The Lancet, 386(10011), 2442-2444.

Mainuddin, A. K. M., Begum, H. A., Rawal, L. B., Islam, A., & Islam, S. S. (2015). Women empowerment and its relation with health seeking behavior in Bangladesh. Journal of family & reproductive health, 9(2), 65.

Ordóñez-Barba, G., & Silva-Hernández, A. (2019). Progresa-oportunidades-prospera: Transformations, reaches and results of a paradigmatic program against poverty. Papeles de Poblacion, 25(99), 77–112. https://doi.org/10.22185/24487147.2019.99.04

Presidencia de la República, (2014), Decreto por el que se crea la Coordinación Nacional de PROSPERA Programa de Inclusión Social, México. DOF – Diario Oficial de la Federación. Available at: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5359088&fecha=05/09/2014 (Accessed: 11 February 2021).

Rivera, J. A., Sotres-Alvarez, D., Habicht, J. P., Shamah, T., & Villalpando, S. (2004). Impact of the Mexican program for education, health, and nutrition (Progresa) on rates of growth and anemia in infants and young children: A randomized effectiveness study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(21), 2563–2570. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.21.2563

Sedesol. (2012). Oportunidades, 15 years of results. www.oportunidades.gob.mx Available at: https://www.heart-resources.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Government-of-Mexico-2012-.pdf (Accessed: 09 February 2021).

Scheel, I., Scheel, A. and Fretheim, A. (2020) “The moral perils of conditional cash transfer programmes and their significance for policy: a meta-ethnography of the ethical debate”, Health Policy and Planning, 35(6), pp. 718-734. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa014.

Sen A. (1999) Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Skoufias E, Davis B, de la Vega S. (1999) Targeting the poor in Mexico: an evaluation of the selection of households for PROGRESA. Discussion Paper Briefs. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)

Skoufias, E. (2005). PROGRESA and its impacts on the welfare of rural households in Mexico (Vol. 139). Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

Sumriddetchkajorn, K. et al. (2019) “Universal health coverage and primary care, Thailand”, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97(6), pp. 415-422. doi: 10.2471/blt.18.223693.

United Nations (UN) (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (Accessed: 13 February 2021).

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2015). The Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3 (Accessed: 6 February 2021).

Victora, C. G., Wagstaff, A., Schellenberg, J. A., Gwatkin, D., Claeson, M., & Habicht, J. P. (2003). Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: More of the same is not enough. In Lancet (Vol. 362, Issue 9379, pp. 233–241). Elsevier Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13917-7

Walsham, G. (2020) Health information systems in developing countries: some reflections on information for action, Information Technology for Development, 26:1, 194-200, DOI: 10.1080/02681102.2019.1586632 Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02681102.2019.1586632?journalCode=titd20

Lamanna, F. (2014). A model from Mexico for the world. World Bank News, 19. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/11/19/un-modelo-de-mexico-para-el-mundo (Accessed: 30 January 2021).

World Health Organization. (1978). Primary health care: report of the International Conference on primary health care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. World Health Organization.

World Health Organization, (2005) Resolution WHA58.33. Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance. In: 58 World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16-25 May (2005). Volume1.Resolutions, decisions,Annexes. (WHA58/2005/ REC/1).

World Health Organization, 2007. Everybody’s business–strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action.

World Health Organization. (2010). Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: a Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies. In World Health Organization (Vol. 35, Issue 1). www.iniscommunication.com

WHO | Health systems service delivery. Available at: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/delivery/en/ (Accessed: 13 February 2021).

World Health Organisation | Q&As: Health systems (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/topics/health_systems/qa/en/ (Accessed: 31 January 2021).

To what extent social science is appropriate as an alternative to epidemiological methods when studying health risks?

(Originally submitted as coursework towards my Masters in Global Public Health at the University of Manchester)

Social science approaches to research differ from epidemiological approaches in a number of ways. Whilst epidemiological approaches are deductive (that is, typically starting with a hypothesis to be proven or disproven) quantitative, social science methodologies may typically be inductive (beginning with an observation that may result in a hypothesis being created), and qualitative. The two approaches are still regarded by many researchers as incompatible means for knowledge construction (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2003).

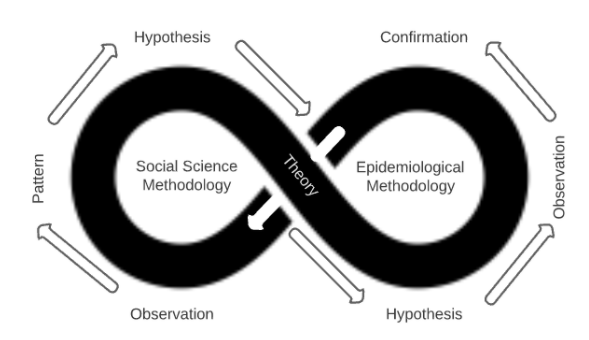

Both approaches align with the scientific method: methodologies are explained so that studies may be understood and replicated by others, results are presented clearly, and conclusions are stated. The two approaches could be considered complementary to each other, each providing the foundation for further research and generation or confirmation of hypotheses as in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: The complementary nature of Social Science and Epidemiological Methodologies.

The 2013-2015 ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone presented urgent clinical and epidemiological challenges, whilst cultural, sociological and political aspects complicated and compounded the situation.

Park et al (2015) analysed sequences from 232 patients in Sierra Leone, along with 86 previously released genomes from earlier in the epidemic, in order to establish whether the virus was being transmitted inter or intra-country. The study took 7 months to complete and provided strong evidence showing that ebola transmission was primarily within-country, not between-country. This provided decision makers with actionable rationale for controlling the movement of people; however it did so only after a full 7 months, by which time over 9,430 cases had been reported (CDC 2017 data).

Ebola is transmitted via bodily fluids including blood, faeces and vomit. The cause of death includes hemorrhaging from orifices and the skin, and as a result, the corpses of ebola victims are highly infectious. In Sierra Leone, washing a corpse prior to burial and touching a corpse during a funeral are common and important elements of local funeral traditions (Richards et al, 2015). Therefore, it was important to quickly understand how to reduce the ebola infection rates related to funerals and burials, and how safe medical burials may be encouraged through understanding local beliefs and practices.

Lee-Kwan et al (2017) carried out a rapid qualitative assessment using focus group discussions that explored community knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards safe and dignified burials in seven chiefdoms in Bo District, Sierra Leone. The study took place over the week of October 20th, 2014, and identified perceived barriers to accepting safe burials that were then used to inform emergency response teams with the goal of reducing transmission of the disease. In less than a month, this data was accessible by aid workers and humanitarian agencies who were able to improve the way they worked with affected communities and slow the spread of the disease.

These examples show that whilst an epidemiological approach provided valuable, precise, and reliable confirmatory data regarding the spread of ebola, a social science approach provided rapid, actionable information that could be used to slow the spread.

Social science methodologies that use qualitative assessments, despite a potential for lower reliability and validity, can generate rapid and actionable insights. This is where the RAR (Rapid Assessment and Response) emerges. RAR is not a single method but a collection of largely qualitative tools, such as interview guidelines and surveys, designed for a particular public health issue. RARs utilise the strengths of social science methodologies such as highly contextual, informal and rapid data gathering to identify existing resources and opportunities for intervention, and help plan, develop and implement interventions and programmes. (Boyce et al, 2004). The goal of a RAR is “to accumulate just enough information to be able to assess whether a particular problem is occurring and how this may be resolved.” (McKeganey, 2000). RARs, and other social science approaches, possess strengths in being able to utilise local expertise, tools and resources which improves cost-effectiveness and provides training for the local community to mitigate health risks. Additional RAR guides are available specifically for use in other health issues, such as working with vulnerable young people (Malcolm & Aggleton, 2004).

Some practitioners and policymakers may see qualitative research, RARs in particular, as weaker in validity than quantitative methods, though it should be seen as an indicator reliable enough to start effective health promotion interventions. (Trautmann & Burrows, 1999)

Not only can social science methodologies provide more rapid data and actionable outcomes, but these types of research methods have an unrivalled capacity to constitute compelling arguments about how things work in particular contexts. (Mason, 2002) Social science methodologies can “explore the perspectives, experiences, relationships and decision-making processes of human actors within health systems, and in so doing, help uncover and explain the impact of vital but difficult-to-measure issues such as power, culture and norms” (Topp et al, 2018).

However, in the power of highly specific context resides a weakness: quantitative evidence possesses less validity in different contexts to the original study, thus it is more difficult to transpose findings into different contexts. It is also more difficult to control for a variety of biases such as recallability or framing, with such methodologies.

Combining social science and epidemiological methods can be powerful. A mixed-method approach can provide the means to more accurately target qualitative research studies. For example, Wilson et al (2016), used an epidemiological approach to analyse cell phone data to rapidly identify population displacement from affected areas in Nepal after the 2015 earthquake. This quantitative data was used to direct, triangulate and strengthen the findings of immediate aid and further qualitative studies.

The essential rationale of the mixed methods approach is that through a multidisciplinary approach that combines qualitative and quantitative methods, one can utilise their respective strengths and escape their respective weaknesses (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998) (From Lund, 2012).

When studying health risks, social science approaches can provide rapid, actionable data, deep context, and additional benefits to the communities in question. Quantitative epidemiological approaches provide greater validity and reliability, and may facilitate more robust decision making. Ultimately, a mixed-methodology approach provides actionable, context-rich data in the shortest possible timescale.

Word Count: 988

References:

Boyce, P. & Aggleton, P. with Malcolm, A. (2004). Rapid assessment and response adaptation guide on hiv and men who have sex with men. WHO/HIV/2004.14 2004 Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/rar/en/ (Accessed: 12 November 2020).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2017). 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa Epidemic Curves. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/cumulative-cases-graphs.html (Accessed: 12 November 2020).

Lee-Kwan, S.H., DeLuca, N., Bunnell, R., Clayton, H.B., Turay, A.S. and Mansaray, Y., (2017). Facilitators and barriers to community acceptance of safe, dignified medical burials in the context of an Ebola epidemic, Sierra Leone, 2014. Journal of health communication, 22(sup1), pp.24-30.

Lund, T., (2012). Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: Some arguments for mixed methods research. Scandinavian journal of educational research, 56(2), pp.155-165.

Malcolm, A & and Aggleton, P. (2004). Rapid assessment and response Adaptation guide for work with especially vulnerable young people. WHO/HIV/2004.15. 2004. Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/en/youngpeoplerar.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed: 12 November 2020).

McKeganey, N., (2000). Rapid assessment: really useful knowledge or an argument for bad science?. International Journal of Drug Policy, 1(11), pp.13-18.

Park, D.J., Dudas, G., Wohl, S., Goba, A., Whitmer, S.L., Andersen, K.G., Sealfon, R.S., Ladner, J.T., Kugelman, J.R., Matranga, C.B. and Winnicki, S.M., (2015). Ebola virus epidemiology, transmission, and evolution during seven months in Sierra Leone. Cell, 161(7), pp.1516-1526.

Richards, P., Amara, J., Ferme, M.C., Kamara, P., Mokuwa, E., Sheriff, A.I., Suluku, R. and Voors, M., (2015). Social pathways for Ebola virus disease in rural Sierra Leone, and some implications for containment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 9(4), p.e0003567.

Tashakkori, A. and Teddlie, C. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Topp, S.M., Scott, K., Ruano, A.L. and Daniels, K., (2018). Showcasing the contribution of social sciences to health policy and systems research. Int J Equity Health 17, 145

Trautmann, F. & Burrows, D., (1999). Conditions for the effective use of rapid assessment and response methods, Marrickville: International Journal of Drug Policy.

Wilson, R., zu Erbach-Schoenberg, E., Albert, M., Power, D., Tudge, S., Gonzalez, M., Guthrie, S., Chamberlain, H., Brooks, C., Hughes, C. and Pitonakova, L., (2016). Rapid and near real-time assessments of population displacement using mobile phone data following disasters: the 2015 Nepal Earthquake. PLoS currents, 8.